As the definitive regime of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) approaches in 2026, governments are beginning to respond, for example the UK is advancing its own carbon border adjustment. At the same time, several countries in the Global South, together with China, have voiced concerns about the potential impacts of CBAM on trade and climate multilateralism.

What is CBAM?

In 2020, the EU raised its climate target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030, based on 1990 levels. To achieve this, the European Commission (EC) introduced the Fit for 55 package, a comprehensive overhaul of climate and energy policies that includes strengthening the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and introducing CBAM for imports of carbon-intensive goods.

CBAM is a carbon pricing tool designed to maintain a level playing field for European companies that are subject to the EU’s compliance carbon market, the EU ETS. It does so by imposing an equivalent carbon price on imports but, if a carbon price has already been paid during manufacturing, importers are entitled to deduct an equal amount.

CBAM’s transitional implementation phase came into force in October 2023 and will last until December 2025. It requires in-scope businesses to report on the embedded direct and indirect emissions of the goods they import into the EU market.

The definitive phase will then begin in 2026, while the purchase of CBAM certificates is set to start in 2027, according to the latest simplification proposed by the EC. CBAM certificate prices will be determined by the weekly average auction price of EU ETS allowances.

CBAM’s scope

CBAM covers 99% of greenhouse gas emissions within its scope, yet exempts approximately 90% of importers due to a de minimis threshold of 50 tonnes per year which aims to ease the burden on importers of a smaller size. This exemption, however, does not apply to hydrogen and electricity. The sectors currently affected include:

- Cement

- Iron and steel

- Aluminum

- Fertilizers

- Hydrogen

- Electricity

The introduction of CBAM, alongside the gradual removal of free ETS allowances, is expected to trigger significant changes in global steel trade flows, as the EU is the world’s largest steel importer, with imports reaching 38.9 million metric tonnes in 2024. It will also create opportunities in the low-carbon fertilizer and hydrogen markets.

By 2030, the scope of CBAM is expected to expand to include all product groups covered by the EU ETS as well as products at risk of carbon leakage, such as other non-ferrous metals apart from aluminum, including copper and zinc among other product categories.

How is the world exposed to CBAM?

The Aggregate Relative CBAM Exposure Index, developed by the World Bank (Figure 1), identifies those countries most exposed to CBAM by assessing the intensity of carbon emissions and the export of CBAM-covered products to the EU. It shows that relatively low-emission exporters will gain competitiveness, despite the requirement to purchase certificates, while countries with carbon-intensive exports will remain the most vulnerable. Mozambique serves as an example of this with 6.9% of its GDP impacted by CBAM, largely due to a 73.7% EU share of exports of CBAM products, with aluminum being its most exposed product.

Figure 1: Aggregate Relative CBAM Exposure Index. Green signifies an improvement in relative competitiveness, while red indicates a decline.

Source: World Bank

What has been the global response so far?

While some jurisdictions, such as the UK, are in the process of introducing their own CBAMs, several developing countries have argued that such mechanisms run counter to the core principles of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement, namely the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities.

In response to these concerns, a recent publication by Harvard’s Belfer Centre suggests that the definition of an effective carbon price under CBAM could be expanded to include investment in decarbonization. By recognising the retirement of certified “carbon tax assets” – representing emissions reductions from high-quality projects – corporations would then be able to use these carbon tax assets to offset their “carbon tax liabilities” under CBAM.

If CBAM and other future border carbon adjustments were to permit the use of certified carbon tax assets to offset carbon tax liabilities, this could significantly enhance climate finance flows to the Global South.

In support of this view, a recent report by the consulting firm Boston Consulting Group estimates that the implementation of CBAM could drive demand for durable carbon dioxide removal up to 550 megatons by 2050.

The CBAM Support Index, developed by Rahat Sabyrbekov and Indra Øverland reveals significant variations in the carbon intensities that are linked to economic performance, suggesting that wealthier countries may be more inclined to support CBAM given their lower carbon intensity and greater potential for innovation.

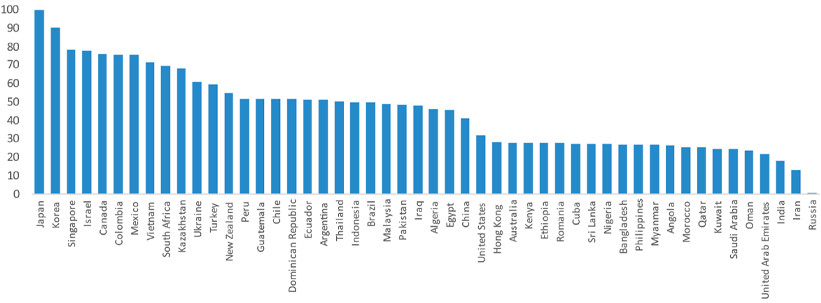

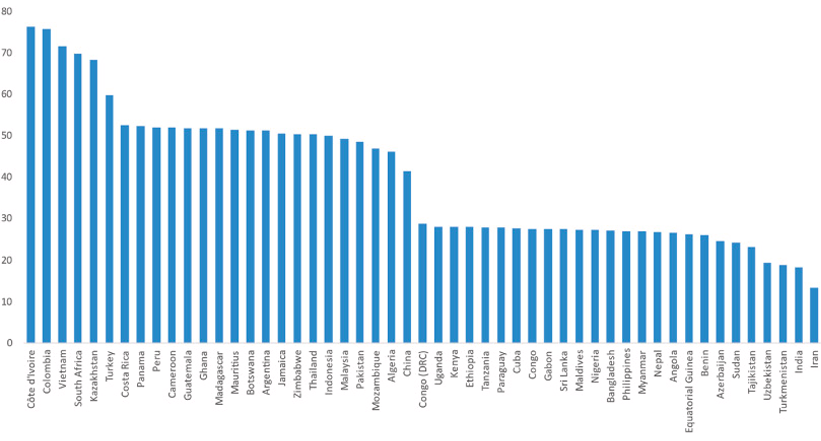

Figure 2 demonstrates that Japan, Korea, and Singapore are the most likely supporters of CBAM among the world’s major economies, while Figure 3 suggests potential support from recipients of EU development aid.

Support for CBAM in certain countries may stem from their high capacity for innovation or from existing domestic policies that align with the proposed carbon pricing mechanism. Additionally, support could be driven by strong historical ties with the EU that are reflected in long-standing trade agreements or EU development assistance.

Figure 2: CBAM Support Index among the fifty largest economies. Scale from 1 to 100, where 1 is the lowest support and 100 is the highest.

Source: ScienceDirect

Figure 3: CBAM Support Index, recipients of EU development aid. A higher score indicates higher potential support of CBAM.

Source: ScienceDirect

Balancing carbon pricing and support for developing countries

CBAM promotes decarbonization overseas by requiring firms to pay for their emissions, while simultaneously encouraging foreign governments to adopt carbon pricing tools and policies to advance decarbonization and prevent revenue loss to the EU.

However, it may impose significant burdens on those low- and middle-income countries that lack the financial means to invest in hard-to-abate sectors.

This highlights the need for increased access to climate finance and EU support to partner countries in the Global South through technical assistance, capacity building, and financial resources via the Global Gateway initiative.