Fertilizers are essential for producer Fernando Barbosa’s coffee plantation to grow and generate quality grains but sourcing the product on the market has never been so difficult since he began farming. Chemical fertilizers work like a type of compost and are used to prepare and stimulate the land ready for planting. However, prices of fertilizer have more than doubled this year and threaten the 2022 harvest among producers in Brazil and throughout Latin America.

“All the fertilizer stock ordered is delayed. If we don’t have time to prepare the soil with the necessary nutrients, the coffee plantation runs a very serious risk,” Barbosa told DevelopmentAid.

The lack of fertilizers may impact production because farmers make purchases in advance, for instance, the product being used today on the plantations was bought in 2020. For small producers, responsible for 80% of the production of fruits and vegetables in Brazil, this crisis is already the main reason for the increase in costs.

The state of Minas Gerais, the location of Fernando’s coffee plantation, is the center of coffee production in Brazil which is the world’s largest exporter. Fernando still expects the delivery of around 50% of the fertilizers purchased in the middle of the year. Last year, the producer had already lost 40% of the total crop due to drought.

Now, the coffee producer fears that the harvest will be even lower if imported inputs do not arrive on time.

“It’s a race against time to avoid losses. If we continue in this cycle, the price will only rise for the consumer,” he warns.

The situation is more serious in Brazil because the country is one of the main food exporters around the world. It ranks first when it comes to soy, sugar, and coffee as well as being the second-largest producer of corn. Brazil, however, is far from being able to make the entire agribusiness machine operate on its own without depending on the international market.

To increase the productivity of all these crops, Brazilian farmers need to import around 80% of the fertilizers they use such as phosphate, potassium chloride, and urea, for example. The source of these inputs is concentrated in the hands of a few countries some of whom have been facing problems in maintaining production amid growing global demand.

“It’s a storm that is brewing”, evaluates Christian Lohbauer, the Executive President of CropLife Brazil, an agro association specializing in research and technology that focuses on sustainable agriculture.

Between January and July, of the 23.8 million tons of fertilizers delivered to farmers, 20 million tons were imported with the remainder being produced domestically, according to the National Association for the Diffusion of Fertilizers. Brazil is considered the only major player in agriculture that is dependent on the import of these inputs.

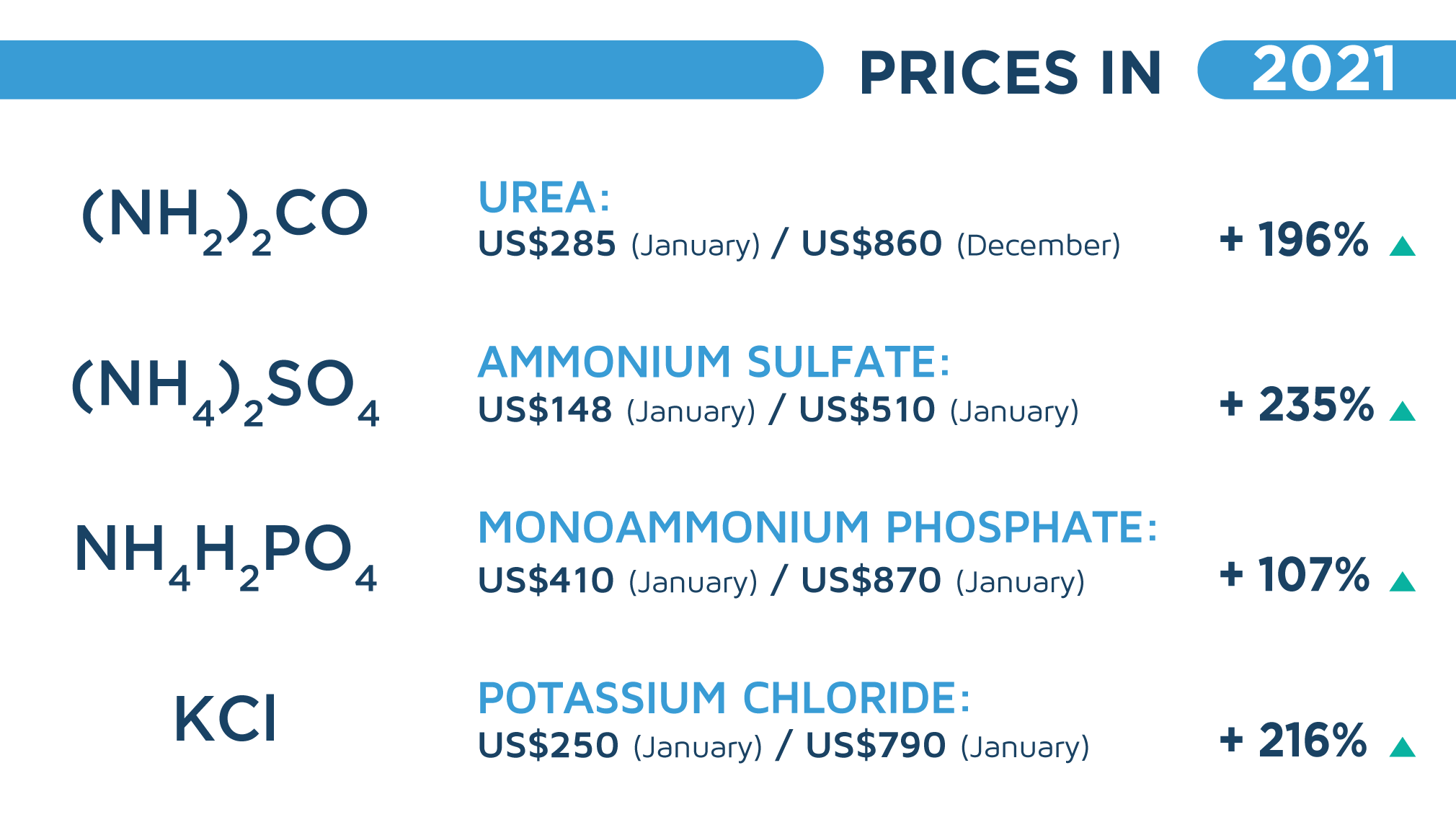

According to the Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock of Brazil (CNA), the fertilizers and pesticides chain accumulated an increase in prices of over 100% in 2021. For example, this year the price of potassium chloride jumped from U$250.00 per ton in January 2021 to U$790.00 per ton in early December.

“The fear is that in the corn crop planting, which starts in 2022 and then in the winter crop, in April to May, and in the next summer crop, scarcity will generate a reduction in planted areas. This impacts the domestic market, but also prices around the world”, Ivan Ramos, Executive Director of Fecoagro, one of the main farmer associations in Brazil, explained to DevelopmentAid.

Three crises in one

The lack of inputs for agriculture is due to three simultaneous global crises. The first is the logistics issue which began with the COVID-19 pandemic when the reduction in the movement of people also compromised the export of goods for industry. In addition to the lack of containers and ships, industries also face shortages of basic items such as packaging.

The second crisis involves the energy sector and in particular China. Nitrogen-based fertilizers, the most important nutrient for crops, are produced through a process that relies on natural gas or coal. There is a short supply of these fuels on the global market, forcing fertilizer plants in Europe to reduce production or, in some cases, close plants altogether.

“China is trying to change its energy matrix, which is dependent on coal which is very polluting, to a renewable one. To meet the country’s environmental goals, the Chinese government is increasing the price of electricity and, as a result, some factories are reducing production,” explains Carlos Eduardo Vian, a Professor at the School of Agriculture, University of São Paulo, in an interview with Development Aid.

In October, the Chinese government decided to reduce fertilizers exports to guarantee domestic supply. Furthermore, all the supplies ready to be shipped to South America had to undergo additional inspection which took exporters by surprise.

“Many of the inputs were not fully in accordance with the certifications and ended up being directed to the domestic market. And even the volumes that had the correct documentation were completely retained”, said a Brazilian professional working in Chinese ports who wished to remain anonymous.

Eastern Europe is responsible for 25% of potassium chloride production globally and, holding one of the largest reserves in the world, in recent decades Belarus has established itself as a major exporter of agricultural products.

However, in May this year President Alexander Lukashenko, who is accused of rigging last year’s elections, forced a commercial flight to crash-land in the nation’s capital in order to arrest one of his opponents. The reaction of the international community was to further increase the sanctions already imposed against the country including a ban on the purchase of potassium from the state-owned Belaruskali.

“When the supply of a product becomes scarce, prices rise, and this has happened with potassium chloride. With the sanctions imposed on Belarus, the market sought potassium chloride in Canada, China, and other countries, generating a rise in sales quotations”, explains Professor Norberto Salomão, a specialist in geopolitics.

The problems could not have come at a worse time for agricultural supply chains. Global food prices have risen more than 30% in the last 12 months to the highest level in a decade, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. At the same time, about a tenth of the world’s population has nothing to eat and with the ongoing fertilizer crisis, the main staple crops of corn, rice, and wheat are even more under threat.