The 2020-2021 tax year was a difficult one for the South African economy as the country grappled with the realities of a hard Covid-19 pandemic lockdown that eroded any small gains that had been made in dealing with the triple threat of inequality, unemployment and poverty.

On the back of this, the country continued to struggle with providing basic services such as water and housing.

It was within this context that fashion designer and social innovator, Carlo Gibson, and live events producer and project manager, Toni Rothbart, joined forces in early 2021 to found make-good, a non-profit company built around identifying societal needs and, through the skills, support and know-how of artisans and makers, using design thinking to develop and create innovative solutions to make people’s lives better whilst simultaneously supporting small businesses in the South African creative sector.

DevelopmentAid spoke with Gibson and Rothbart to find out more.

DevelopmentAid: Please provide a brief overview of the founding of make-good.

Rothbart: We met over a mutual desire to make a difference to the world around us, and the energy to promote change. So, we decided to have a cup of coffee and find a way to channel our skills, capabilities and experience and heart-filled passion for South Africa into making a difference in the world.

We realized that by connecting communities, creative industries and funding with the focus on building a sustainable way to help people, we could “make good”.

DevelopmentAid: What was the motivation for starting the organization?

Gibson: Our aim was to help find solutions to problems that exist in our greater community. We have always understood and been guided by the power of the solutionist thinking of The Maker and so created a model where we work together, harnessing the honed skills and capabilities of our collaborators, their expertise and passion for what they do – to be a part of something, rather than just an outsourced supplier or resource.

We all have our areas of expertise and together we learn new things and new ways of doing things that strengthen each of our own baselines.

Rothbart: The stark implications of COVID-19’s impact in our communities throughout 2020 and 2021 highlighted the increase in displaced persons on our streets in South Africa and even globally, and prompted the need to get our Homeless Home project to market and out on the streets as a matter of urgency.

[Carlo came up with the concept of the Homeless Home project when he was riding a bike on a cold winter morning in Johannesburg and was struck with the idea of making an item of clothing that could be augmented when needed (padded for extra insulation) and the stuffing could be discarded (with minimal impact) when no longer needed.]

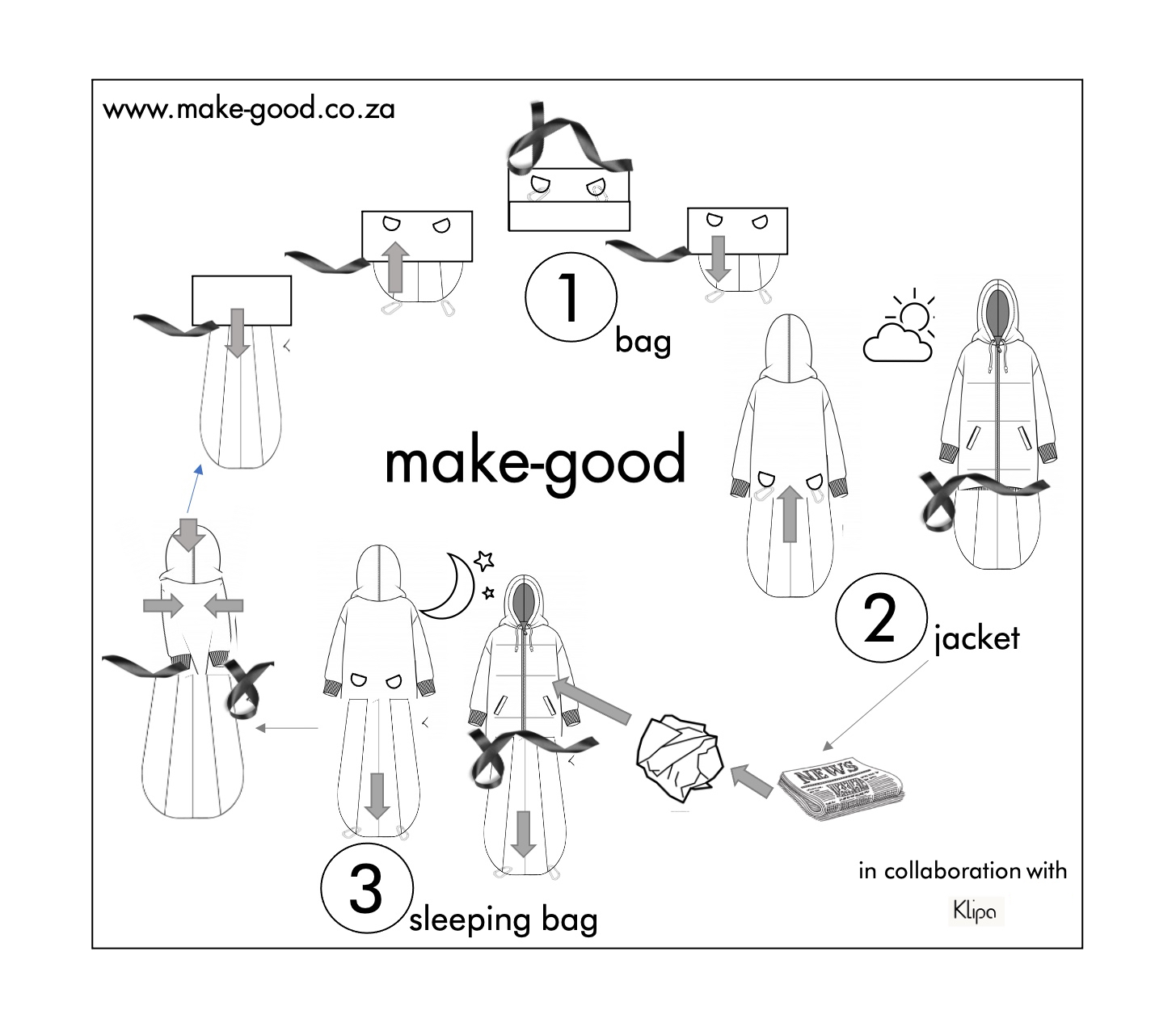

Gibson: The Homeless Home is an item of clothing designed to transform from sleeping bag to jacket and vice versa – so it has to be easy to carry, durable, lightweight, waterproof and windproof – where the wearer can keep using it as a jacket during the day and then a sleeping bag at night.

Gibson: The design has horizontal pockets or pouches which can be stuffed with throw-away items found on the streets – like newspaper – which helps to insulate the jacket for extra warmth, and adds padding to the garment for some comfort when sleeping. It also has some pockets allowing the wearer to carry their most important possessions with them.

DevelopmentAid: What have been some of the quick wins you have had since launching?

Rothbart: We decided to make 100 Homeless Home jackets at the outset – self-funded – and distributed these around Johannesburg to highlight the intention and identify that just by starting something and pitching up, it’s possible to make a difference.

Our efforts received attention from the media and other charities and as a result, we were able to raise funds to cover our input costs and to continue with the cause.

Gibson: We launched in June 2021 and by November we had already distributed almost 600 funded jackets throughout South Africa and had been recognized by TWYG by winning the Innovative Design & Materials Award (presented by adidas) at the 2021 TWYG Sustainable Fashion Awards for The Homeless Home Project.

Rothbart: In July 2021, we started collaborating with another non-profit called COPESSA, which focuses on gender-based violence and violence against children, and together we identified a group of women called The Women of Worth.

With this group, we are trying to find a way, through skills provision in making the Homeless Home, to provide the pathways of independence that are so critical for freedom from abusive situations.

This collaboration was an unexpected direction from what we had set out to do but opened a pathway to expand how we were trying to make good. The intention and creation of this partnership allowed us to be recognized and rewarded and last year we received seed funding from the SAB Foundation.

DevelopmentAid: What criteria do you use to decide which projects to fund?

Rothbart: Projects that meet the criteria of being “a problem to solve” in the greater community and those that can be approached from a solutionist maker’s perspective, to find a solution and create change, appeal to us.

We initially go into the project through our own knowledge and capabilities and then, by interviewing the end users, use design thinking and prototyping to test whether or not the innovation is useful in the ways we understand and what the end user themselves can gain/benefit and what they can add to the ongoing design.

DevelopmentAid: How would you describe the process of registering a not-for-profit organization in South Africa?

Rothbart: It was actually relatively easy at first as we engaged a company to assist us with registering and setting up an NPO and they guided us through the process.

COVID delayed the process a little as government structures were often running on skeleton staff or no-one was allowed to enter the buildings. However, make-good was registered within a few months.

Many facilities – like banks, backabuddy crowdfunding – all have special rates to assist and contribute to raising funds and keeping costs low to benefit nonprofits.

DevelopmentAid: How do you measure success in terms of the company’s focus areas, RoI from funders, and the sustainability of make-good?

Rothbart: Our initial measure was purely quantity, so how many items of the Homeless Home we could get out onto the streets, and also qualitative engagement, whether or not the jackets were helping the people they were intended for.

Gibson: As we continue to engage with more projects and see the impact that our passion has on people who want to make a difference and bring other ideas and concepts to us for development and shaping, this helps to strengthen and direct the organization’s focus

The company is relatively new, with only one project to market so far, but as we continue to develop more initiatives (we currently have two in the pipeline in early childhood development and sustainable nutrition education), we are hoping that each project shows its own wins.

DevelopmentAid: Please can you share data, if available, on the number of people who receive an income from being suppliers to your projects?

Rothbart: We don’t currently have these figures. The project started out as just the two of us, with the intention of helping a cut-make-trim (CMT) factory through the worst of COVID. The CMT employs 20 people and is still running so we hope that our contribution helped them to stay afloat in some of the more difficult, challenging times of manufacture.

Once the collaboration with COPESSA gets off the ground we will initially be providing 15 women with the opportunity to hone their skills and earn sufficient money to support themselves and their children. If this project proves successful, we intend rolling it out to more communities.

DevelopmentAid: Please explain the impact that the products have had on the homeless.

Rothbart: It’s often difficult to get consistent feedback from many of the people we distribute to within this project because of the nomadic nature of the lives of homeless people – they are on this street corner one week, and either choose to move to new neighborhoods or are even forcibly moved.

From the feedback we have received, those we distributed to found the item useful throughout winter, even noting that it was often more difficult times to keep warm and dry in the summer rainfalls.

We found that us returning to the physical location where we initially distributed the jackets often meant a lot more to the communities than the item itself. This talks to the need for people to feel considered, to be seen, to feel valued, and listened to – that, for us was an unexpected, sobering, and humbling experience.

DevelopmentAid: From your point of view, are the measures implemented at the country level enough to help this category of people? Are there any other organizations trying to help? Do these organizations join efforts and coordinate actions for a more powerful impact on the lives of these people?

Rothbart: Traditionally community-based organizations, like churches or rotary clubs, are engaged directly with homeless needs at the ground level.

In our experience, there has not been that much country-level assistance – with municipalities trying harder to fence the homeless out (often arresting and confiscating belongings or private property like identity cards leaving people further disenfranchised) and not trying hard enough to be more inclusive.

We have numerous examples locally of how the homeless can add value to society. For example, informal recyclers who are often homeless go through people’s trash bins for cardboard and cans and then sell these.

There are very few shelters or places of safety for homeless people.

DevelopmentAid: What are some of the challenges you’ve seen that affect the development sector in South Africa?

Rothbart: By its very definition, this sector’s aim is to support and buoy the economic well-being of some of our most vulnerable members of society.

There is growing fatigue and an almost thick-skinned response now to some of our country’s largest problems like gender-based violence, homelessness, poverty, lack of access to proper medical care, and nutritional insufficiencies.

Programs are implemented with good intention and some even create strong awareness, but there is inadequate follow-through. Merely highlighting the plight of people or groups or communities does not have any concrete and measurable effect on the lives of the vulnerable and abused in our society.

The lack of and even sometimes poorly distributed funding also contributes to an overall frustration that there seems to be very little done to support and stimulate the lives of those in need. It seems as if smaller, independent organizations are the ones finding the solutions and keeping the change possible.