The OECD DAC’s new ‘grant-equivalent’ methodology for measuring ODA flows is changing the way development loans are reported as ODA. This Donor Tracker Insights piece sheds light on how the reform has impacted the ODA volume of donors in 2018. It also explains why the reform has so far particularly affected six donors: Japan, Spain, the EU institutions, Germany, France, and South Korea.

What is the ODA loan reform about?

Starting with 2018 data, the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) is using a new methodology to calculate data on donors’ official development assistance (ODA). Called the ‘grant-equivalent,’ the methodology aims to better reflect donors’ real financial effort when disbursing ODA loans. It is the OECD DAC’s new standard for publishing headline ODA figures and has a concrete impact on how much of a donors’ loan can be counted as ODA.

How were loans counted before the reform?

Under the old reporting system, which used a ‘cash-flow basis’ to measure ODA, the full face value of a loan was reported as ODA—as long as its ‘grant-element’ was at least 25%, regardless of the income level of the borrowing country. The grant element of a loan is a measurement of how ‘soft’ or concessional the conditions (e.g., interest rate and grace period) of a loan are and is expressed as a percentage.

When a recipient country later repaid the loan, the repaid amount would be subtracted from a donor’s ODA. ODA figures that discounted the repaid amount were referred to as ‘net ODA’ (vs. ‘gross ODA’, which counted the total amount disbursed by a donor in a given year).

So what changed?

With the new methodology, only the grant-equivalent share of an ODA loan counts towards ODA. The grant equivalent of a loan is its grant element expressed as a monetary value (e.g., in US$). In turn, the repayment of ODA loans is no longer subtracted from ODA headline figures, eliminating the distinction between gross vs. net ODA.

In addition, the minimum grant-element required for a loan to count towards ODA is now differentiated based on the income group of the borrowing country. It must be at least:

- 45% for the groups of low-income countries and least-developed countries;

- 15% for lower-middle-income countries;

- 10% for upper-middle-income countries.

This differentiation by income group was introduced to promote the stronger use of grants and highly concessional (soft) loans in low-income countries.

How does the reform affect comparability?

The introduction of the grant-equivalent methodology means that ODA data for 2018 using the new methodology cannot be directly compared to spending in previous years when the methodology was not yet in use. To allow for comparison of ODA figures over time, the OECD DAC will continue to publish ODA data using the old, cash-flow basis methodology.

How does the reform impact donors’ ODA?

It is still too early to fully assess the impact of the reform on donors’ ODA given that grant-equivalent figures have only recently become the standard.

The OECD’s preliminary data for 2018 indicates that the application of the methodology has led to a small increase in ODA. All 29 DAC member countries combined provided US$153 billion in ODA in 2018 using the new grant-equivalent methodology. This is 2.5% higher than ODA using the

previous cash-flow basis methodology (US$149.3 billion).

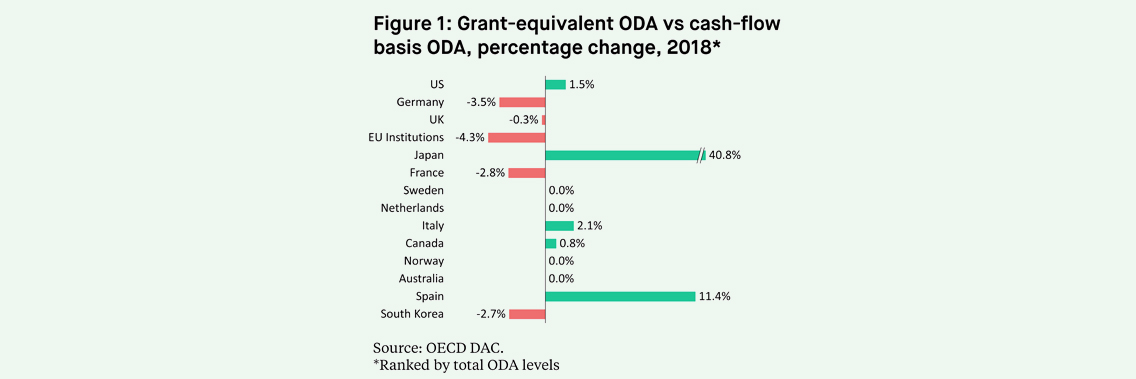

A closer look at the 14 major OECD donors covered by the Donor Tracker reveals more nuances. The reform affected six donors significantly (defined here as a change in ODA by more than 2.5%, which is the percentage change of all DAC donors:

- Japan (+40.8%)

- Spain (+11.4%)

- EU institutions (-4.3%)

- Germany (-3.5%)

- France (-2.8%)

- South Korea (-2.7%)

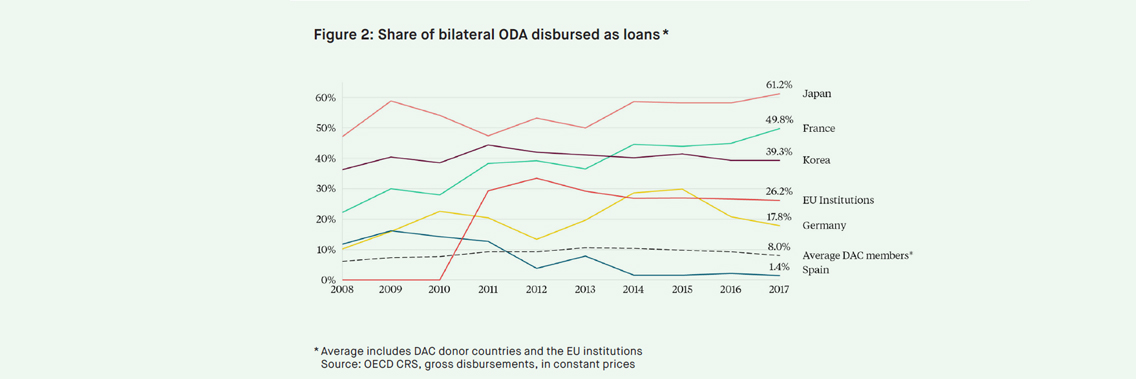

These are all countries that currently disburse large shares of their ODA as loans or have done so in the past.

Follow the link to take a closer look at these six donors and why the ODA loan reform impacts them more than others.