To help anticipate and hence better address marine pollution scenarios in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, scientists from the IAEA and Ecuador have recently completed the first-ever, decade-long study on plastic particle abundance in the coastal waters of Ecuador. The study results form a baseline for future research, including on seafood safety.

The eastern tropical Pacific Ocean is home to some of the world’s unique marine reserves, including the Galapagos Islands in Ecuador, the Cocos Island in Costa Rica and the Coiba National Park in Panama – all included on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites.

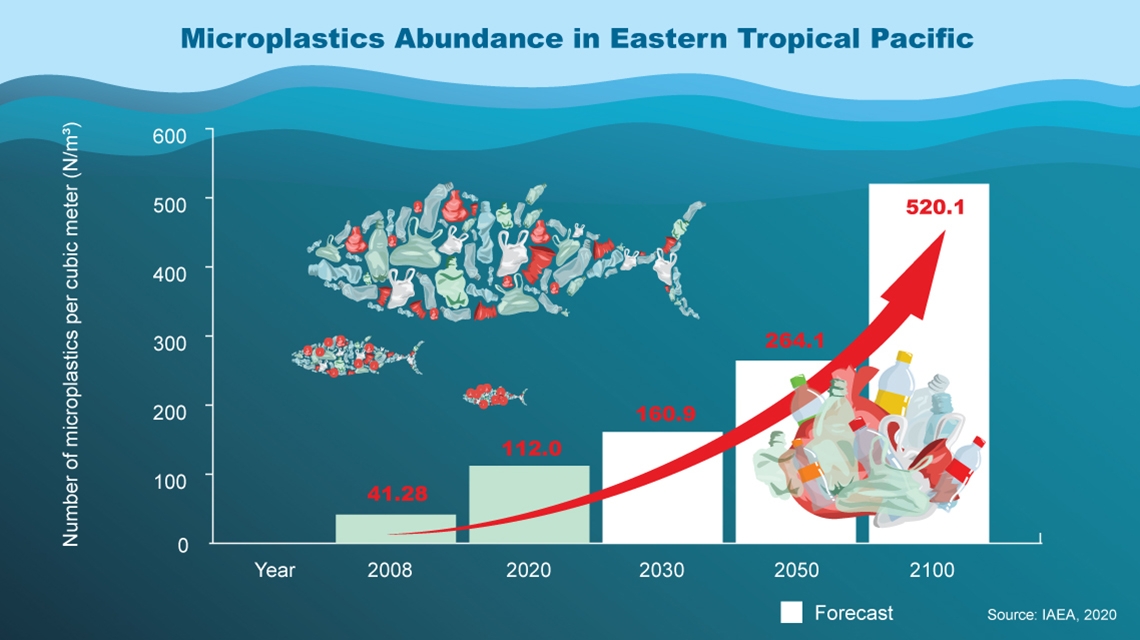

“The research has revealed that the microplastic pollution in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean is set to continue to increase in the coming decades,” said Peter Swarzenski, Acting Director of the IAEA Environment Laboratories.

Plastic particles below 5 mm in length are called microplastics, which are accidentally consumed by marinne organisms and make their way to the food chain, as a recent IAEA study has revealed.

The amount of microplastics in the region is expected by 2030 to increase some 3.9 times compared to 2008 levels. By 2050, this quantity could almost double again, rising by 6.4 times compared to 2008 levels, and by 2100, the amount of plastics in the ocean is projected to be more than 10 times higher than in 2008 unless action is taken to change this trajectory.

One of the crucial findings of this study is that the change in the microplastic abundance over time increases systematically and identically at all the sampling sites. This implies that the source of microplastics pollution is likely not local, but regional and maybe even global in scale. As many of the world’s mega-cities are located near coastlines, adjacent coastal waters are often elevated in marine plastics abundance, which in turn may impact local fisheries and seafood safety.

“It is sad but not surprising to see such a steep increase of microplastic abundance in the region,” said Rafael Bermudez Monsalve, Investigator Scientist from Ecuador supporting the research at the IAEA Environment Laboratories.

Plastics are by design tough and resistant to degradation and have thus over time been found even in the deepest marine trenches. In our oceans, plastic fragments are broken down continuously by ultra-violet light, by the corrosive nature of seawater and by the constant physical erosion due to waves and shear. This continuous degradation supplies a stream of tiny micro and nano-sized plastic particles that can be inadvertently consumed by marine organism and thus introduced into the food chain.

“As we continue to develop our research on marine plastics, nuclear and isotopic techniques are playing a particularly important role in advancing both the science and knowledge on the subtle, sustained impacts of microplastic pollution in the marine realm,” said Swarzenski.

The microplastics under evaluation were classified into three types: fragments (bottles, cups, food containers), fibers (plastic lines and fishing detritus), and film (plastic bags, zip bags). Fibers were found to be the most common plastic particle in the open water. These tiny particles have been found to travel as far as 10 000 kilometers in the Pacific Ocean and have reached even the most remote areas such as Galapagos Islands, polluting its pristine waters and rich wildlife.

Original source: IAEA

Published on 08 June 2020