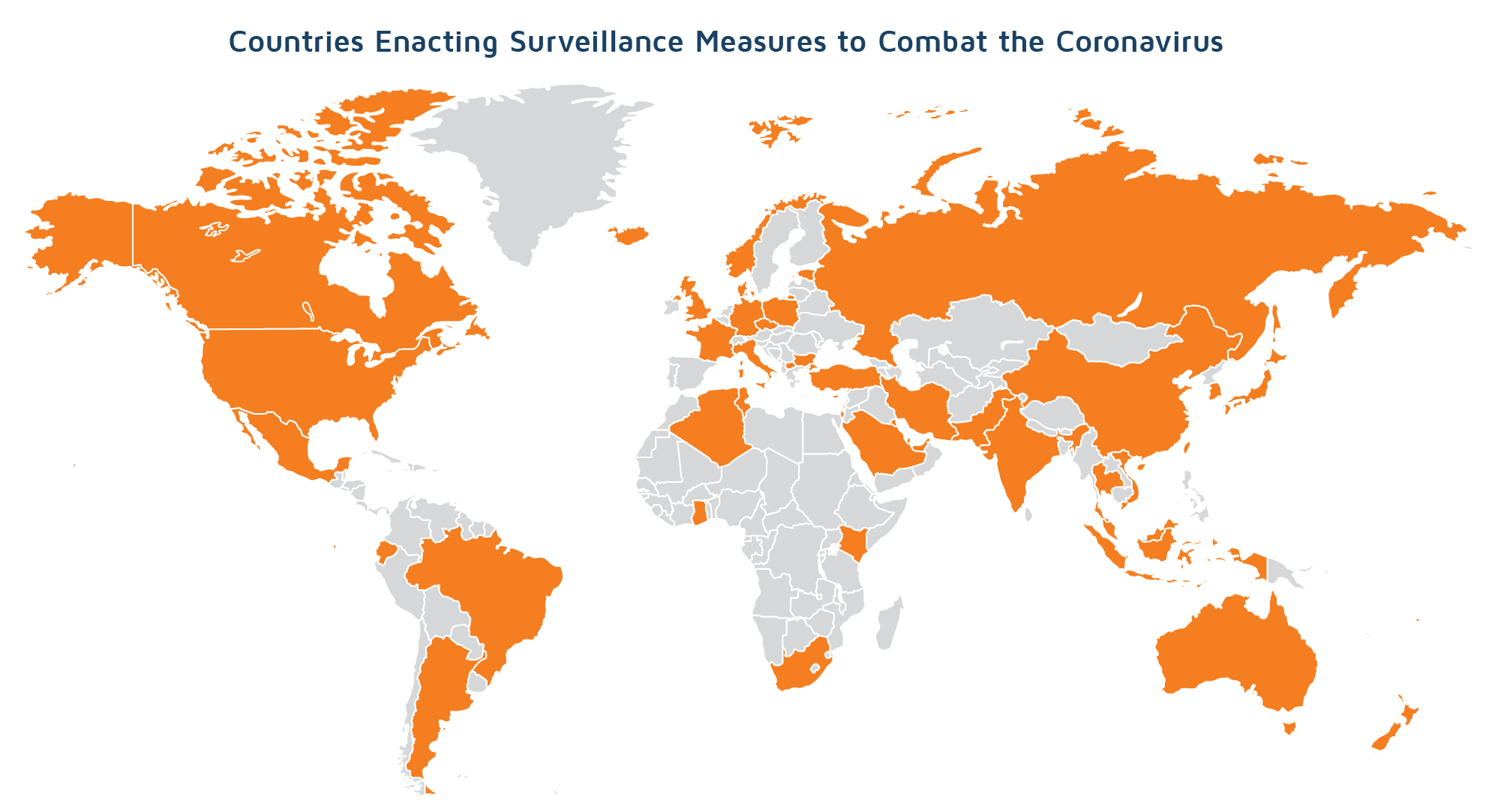

On the grounds of virus containment, a number of governments around the world have opted for increased surveillance of their citizens which some experts consider to be invasive and dangerous. Reports point to the fact that at least 35 countries have deployed some form of invasive surveillance. This present article will review the forms of surveillance applied during COVID-19 and will map those locations around the world who now have increased surveillance measures.

A number of countries have adopted what would normally be considered invasive surveillance methods using the argument of virus containment. The most common form of surveillance is the use of smartphone location data. Location tracking supposes monitoring of population movement and potentially enforcing individual quarantine when there is suspicion of infection. Some governments, such as those in France and the UK have created apps that offer coronavirus health information, while smartphone owners agreeing to share location and health information with the authorities. India is the only country that has made its Aaragoya Setu tracking application mandatory for the government staff and all the employees in the public and private sector.

The use of drones and patrol robots, CCTV cameras and smartphone applications with facial recognition and thermal imaging cameras are some of the other surveillance methods that have been deployed during the pandemic.

Some of the countries that are leading this trend of tech-enabled mass surveillance are China, Israel and South Korea. Israel, a regional cyber-superpower, has co-opted its Security Agency, Shin Bet, in its plan to contain the spread of the virus through the use of technology. In an unprecedented expansion of Shin Bet’s powers, the agency has applied counter-terrorism methods to monitor coronavirus patients and people who have been in contact with them. Based on this data, the government has sent more than 80,000 messages instructing potentially infected citizens to self-isolate and it has made more than 100,000 home checks to confirm compliance. After nearly three months, the controversial Shin Bet program ended early in June but, as a second wave of coronavirus cases is predicted in Israel, the country’s Prime Minister Netanyahu is said to be insisting on the reactivation of the program.

Reports show that so far more than 40 countries in the world have deployed some form of surveillance during the pandemic. Worldwide, 43 countries have developed national smartphone tracking applications. Some of the most alarming measures have been in Argentina where those who break the quarantine are obliged to download an app that tracks their location. In Hong Kong, those arriving at the local biggest airport are given electronic tracking bracelets that must be synced to their home location through their smartphone’s GPS signal.

In Bahrain, citizens who downloaded the BeAware Bahrain tracing app became contestants on a television show. The citizens were live video called to check if they were adhering to social distancing guidelines and offered monetary rewards to those that were.

In a recently released study of location tracing apps, Amnesty International found that some countries are using the apps as tools of mass surveillance. The study analyzed the tracking apps of 11 countries – Algeria, Bahrain, France, Iceland, Israel, Kuwait, Lebanon, Norway, Qatar, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates. It found three particularly invasive apps that collected satellite location data from users rather than simply relying on Bluetooth signals and matched accounts with real identities.

“Bahrain, Kuwait and Norway have run roughshod over people’s privacy, with highly invasive surveillance tools which go far beyond what is justified in efforts to tackle COVID-19,” said Claudio Guarnieri, the head of Amnesty International’s Security Lab.

The discussions following the implementation of these surveillance methods have focused on the issues of privacy and personal freedom. In France, more than 140 French cybersecurity and privacy experts signed a letter warning the public and the authorities about the risks of the country’s contact tracing app. “All these applications involve very significant risks with regard to respect for privacy and individual freedoms. One of them is mass surveillance by private or public actors,” the experts wrote.

Despite the rapid spread of contact tracing apps, there is no evidence to show the effectiveness of location tracing in stopping the virus and nor have governments around the world shown that such increased powers could significantly contribute to the containment of the virus. Most of the apps store the data either on a central server, like in the case of Norway, or in a cloud-based facility, like Australia’s case, as well as on the devices themselves. And although most of them claim that the data will be deleted from the smartphones after a period ranging from 28 to 60 days, in some instances data will not be deleted from the central servers or clouds. Australia’s government claims that the total deletion of personal information from the cloud could only be done upon filling a web form requesting that. Most of the governments state that the apps will be in use until the pandemic will be declared over.

“Time and again, governments have used crises to expand their power, and often their intrusion into citizens’ lives. The COVID-19 pandemic has seen this pattern play out on a huge scale.”, states the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a leading NGO defending civil liberties in the digital world. Civil society groups, like the EFF, fear that such considerations point to a future where tech-based surveillance could become an unstoppable trend, with Covid-19 being the turning point. “Like other emergency measures, it may be an uphill battle to roll back new location surveillance once the epidemic subsides.”

Stay tuned for more articles covering the COVID-19 topic and its influence on the international development sector, by subscribing to the DevelopmentAid newsletter.