Economic breakdown, high rates of unemployment, disruptions to global supply chains and cuts to humanitarian aid have trapped people in poverty and hunger. Around 12,000 people per day could die due to the acute hunger crisis linked to the pandemic, a higher mortality rate than that caused by the disease itself. In reality, more people could die from lack of food rather than from the disease before the end of the year.

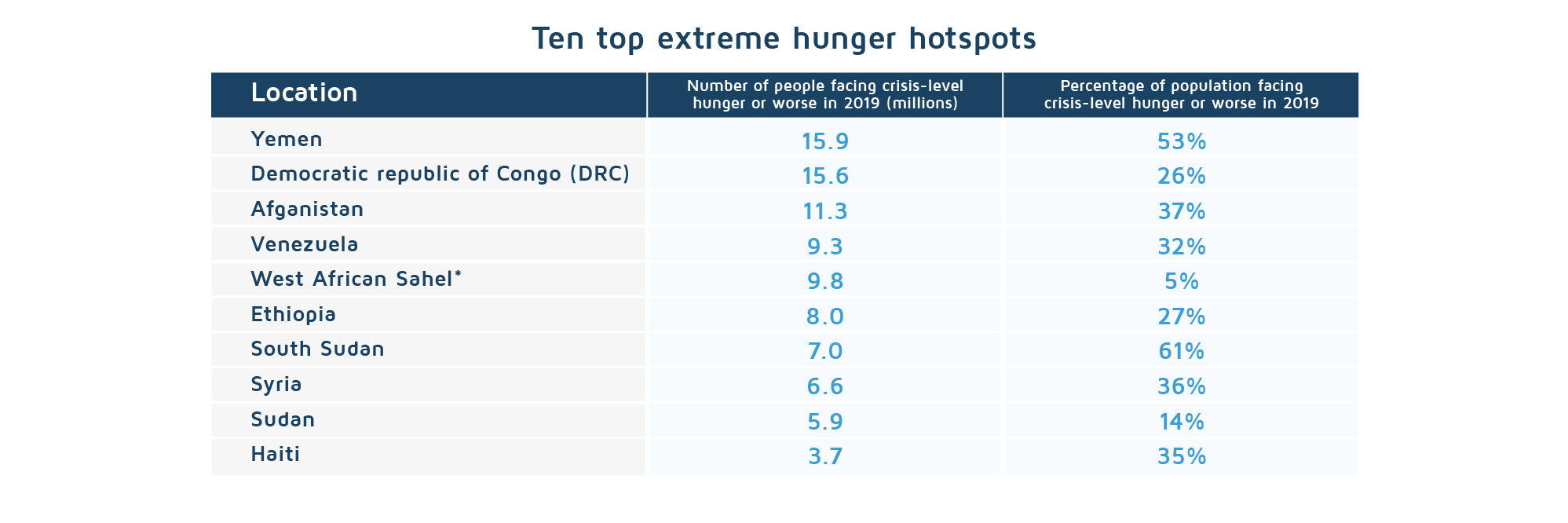

Even before the pandemic, food insecurity rates had raised concerns within the international community. The World Food Programme has forecast an 82% increase in the number of people experiencing hunger, accounting for 270 million, by the end of the year. Millions of people are joining the ranks of those who face starvation as a result of huge unemployment rates and the economic disruption caused by the pandemic. The devastating repercussions associated with the novel coronavirus have deepened the food insecurity crisis in countries that were already facing acute food shortages. The ten extreme hunger hotspots analyzed by Oxfam in its most recent report, account for 65% of the total population in crisis.

Conflicts drive hunger to worrying levels

Of those 821 million people threatened by hunger in the world, about 60% of them and 80% of stunted children live in countries affected by conflicts and wars. Eight of the ten extreme hunger hotspots listed above are affected by high levels of violence and insecurity. The ongoing conflict in Yemen has consigned two-thirds of the population, 20 million people, to face hunger and nearly 1.5 million families have become dependent on food aid to survive. As a result of the restrictive measures related to COVID and their combined repercussions, 80% of remittances have dropped by 80%.

Food crisis is worsening

West African Sahel is one of the hottest hunger spots where famine, violence and climate crisis have been exacerbated by the novel coronavirus and about 11 million people are estimated to be in immediate need of food assistance in the region. The new realities created by the pandemic point to another 51 million people potentially experiencing an acute food crisis. Around 2.5 million children aged under 5 years of age in the Sahel have suffered from severe malnutrition.

Before the pandemic, over 60% of people in South Sudan faced crisis levels of hunger and as a result of the outbreak, food insecurity has consistently deteriorated. More than 7.5 million people are dependent on humanitarian aid which has been significantly reduced as a result of severe underfunding and the disruptions to food supplies make their lives virtually unlivable. The delays in providing food supplies have also contributed to a 40% spike in food prices.

Emerging hunger hotspots

Oxfam warns that new hunger hotspots are emerging such as India, South Africa and Brazil where the levels of food insecurity are rising rapidly leaving millions of people facing starvation. Around 8 million workers in Brazil have lost their jobs or incomes and the employment rate has fallen to 49.5%, the lowest since 2012. Despite the necessity for urgent basic needs to be met, the Brazilian government has distributed less than a half of the funds allocated to emergency assistance for vulnerable people. Moreover, the way in which the pandemic has shrunk the country’s economy over the last three months has led to the government threatening to reduce benefit payments.

Reducing stunting, an ambitious mission

Social distancing has resulted in job losses in India where nearly half of the population have lost their income with this particularly affecting the most vulnerable households. Despite the fact that the Indian government has announced a US$22.5 billion aid package, millions of the most vulnerable people have been unable to access assistance and around 95 million children from poor communities have been deprived of midday meals at schools. Coronavirus has placed additional pressure on the government, making it harder to reach the World Health Organization’s target of reducing stunting by 50% by 2030. Maternal and child malnutrition is one of the reasons for 68% under-five deaths in India.

Governments, even the wealthiest ones, should take concerted action to end hunger in a world that produces more than enough food for everyone. Many of them are seeking to alleviate the unprecedented repercussions of the pandemic that have pushed people into poverty by expanding their existing protection policies, providing income replacement for the most vulnerable households, developing short-time work compensation schemes and offering access to various significant fiscal packages. Meanwhile, other are failing to provide their people with live-saving solutions which could prevent famine of worrying proportions.

DevelopmentAid tracks the most important news and events. Subscribe to DevelopmentAid and gain access to up-to-date information.