5 key reasons to read this article

- Understand how one political decision set off a chain reaction that dismantled decades of global humanitarian infrastructure in less than a year.

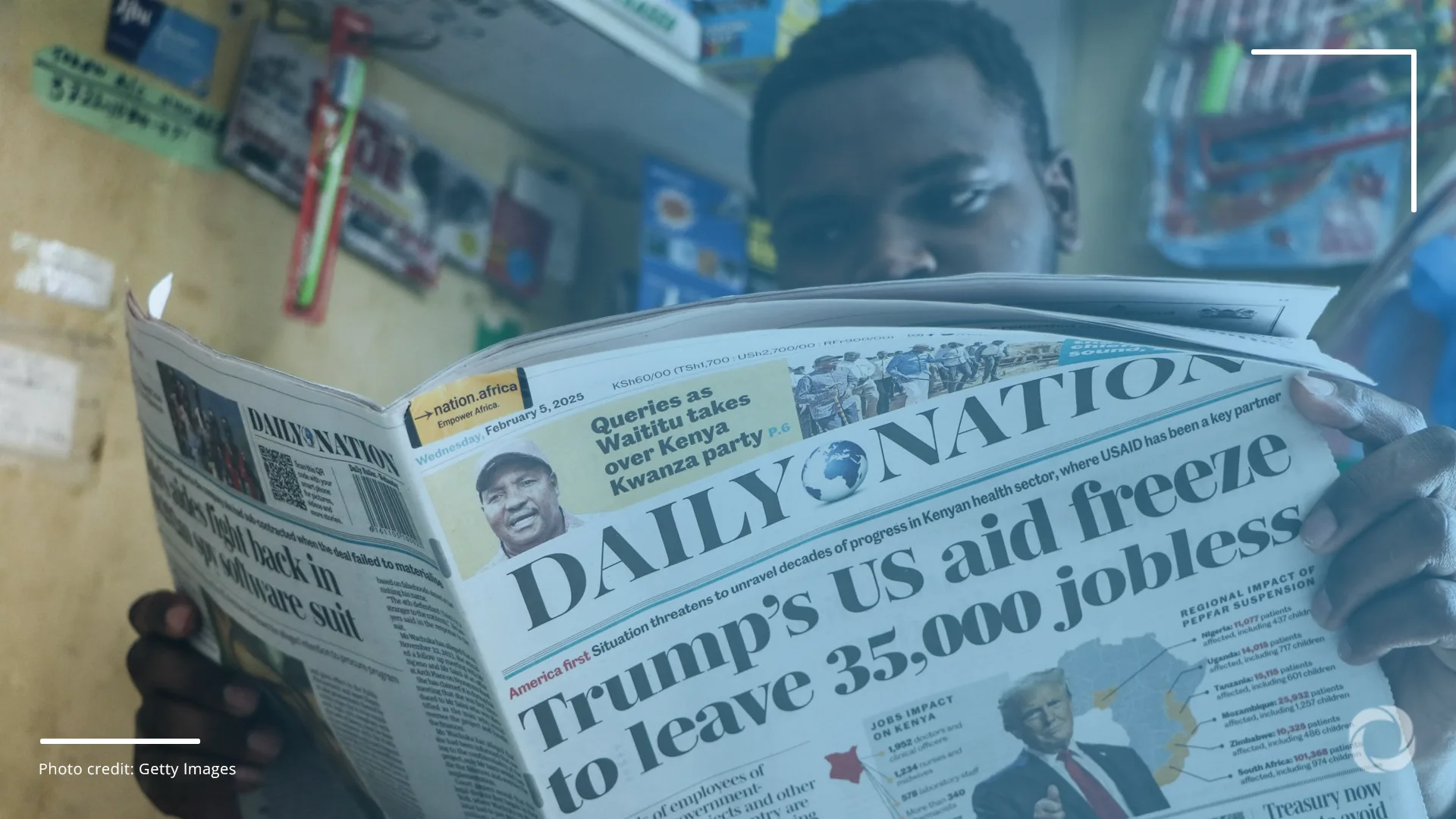

- Learn why tens of thousands of aid workers suddenly lost their jobs.

- Find out how humanitarian aid quietly shifted from offering life-saving support to being a tool of political and military control.

- Examine what happens when the world’s largest donors walk away.

- Delve into a new era of aid where millions in need will be deprioritized, and survival itself will no longer be guaranteed.

The year 2025 will be remembered as a seismic turning point for global humanitarian aid.

What began on January 20, when U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order halting foreign assistance from the world’s largest donor, quickly sent tremors throughout the entire aid architecture. The move triggered mass layoffs, donor withdrawals, and the weakening of multilateral institutions built over decades, according to humanitarian agencies and donor data released during 2025.

By March, the UN’s Emergency Relief Coordinator Tom Fletcher issued a stark warning that a ‘humanitarian reset’ was underway. With just four years remaining to meet the Sustainable Development Goals, the fractures exposed in 2025 did not threaten simply indicate a temporary disruption but signaled a fundamental reordering of how, and whether, the world would respond to humanitarian crises.

Here are the major events that reshaped humanitarian aid in 2025.

1. The USAID Earthquake

In January, Trump dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development through an executive order, describing it as “wasteful, inefficient, and no longer aligned with America’s interests”.

The order froze foreign aid, cancelled the majority of contracts, and folded USAID into the State Department. By July 1, USAID, previously the world’s largest foreign aid agency, accounting for more than 16% of global official development assistance (ODA), officially closed after over 90% of its programs were terminated, eliminating more than US$40 billion in aid.

The scale of the loss was staggering. USAID’s programs operated in more than 150 countries and reached over 150 million people annually, funding food aid, emergency relief, vaccinations, HIV/AIDS treatment, maternal and child health, and refugee support.

The Lancet medical journal has warned that, under worst-case modelling scenarios, sustained cuts could lead to over 14 million preventable deaths by 2030, including millions of children.

2. Unprecedented Western donor cuts

The US cut triggered the sharpest contraction in Western aid budgets in decades. ODA across Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development donors fell by about 6% in 2024 from roughly US$214.5 billion and is projected to have declined by a further 9–17% in 2025, according to OECD statistics.

Belgium plans a 25% cut in ODA, France slashed core ODA by 18%, Germany cut roughly €4.8 billion between 2022 and 2025, and the UK announced a gradual reduction of aid from 0.5% of GNI in 2025 to 0.3% in 2027. Governments have cited fiscal pressure, domestic priorities, and security concerns as being the key drivers of these decisions.

These shifts were driven partly by the war in Ukraine and broader security concerns, which drove countries to direct aid to defense. European defense budgets surged, with Germany spending over €90 billion, approximately 2.1% of GDP, and France increasing defense outlays to more than €59 billion, around 2% of GDP in 2024, as countries prioritized military readiness in a tense geopolitical climate.

3. Mass layoffs

As funding collapsed, humanitarian employment followed, with job losses reaching historic levels. A sector-wide lay-off tracker found that at least 233,818 humanitarian jobs had been lost across 159 agencies, including nearly 20,000 in the United States, by mid-year, with this figure continuing to rise as funding dried up.

More than 31,000 jobs were cut across eight UN agencies, eight international NGOs, and the International Committee of the Red Cross, according to analysis by the UK-based global non-profit ALNAP. A survey by the Somalia NGO Consortium, cited by ALNAP, found that 95% of local organizations in some contexts reported layoffs, and three-quarters had closed offices or project sites by late 2025.

4. United Nations under strain

The funding shock reverberated throughout the United Nations system. Secretary-General António Guterres warned that unpaid member-state dues had risen to nearly US$1.6 billion, forcing the organization to operate below approved levels.

The announcement in December by the U.S. of a US$2 billion pledge for UN humanitarian aid, down from contributions of up to US$17 billion in recent years, highlights this year’s most noticeable commitment retreat.

Major agencies announced sweeping cuts, with the World Food Programme reducing its workforce by 30%, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees eliminating around 30% of staff, including half of senior posts, and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs laying off roughly 500 employees.

Under the UN80 reform initiative, Guterres proposed cutting the 2026 regular budget by US$577 million and eliminating 2,681 posts, nearly one-fifth of current staffing, while at the same time merging departments and streamlining operations.

Plans include consolidating mandates, the proposed mergers or closures of certain agencies such as UNAIDS, and relocating functions from high-cost hubs such as Geneva to regional centers, including Nairobi, where operations for the UN Children’s Fund and UN Women are set to expand.

5. Politicization and militarization of aid

In 2025, humanitarian aid increasingly became a tool of political control. The US-backed Gaza Humanitarian Foundation exemplified this shift. In Gaza, it fundamentally altered aid delivery by asserting exclusive control over medical and food assistance, sidelining established NGOs and UN agencies.

Aid distribution, traditionally governed by neutrality, impartiality, and independence, became conditional on political alignment and local control, with humanitarian actors describing the system as the militarization of aid, enforced through security-linked structures that restricted independent oversight.

At the same time, the U.S. America First Global Health Strategy reframed assistance as commercial diplomacy. The policy directed funding toward the procurement of American-made medicines, diagnostics, and technologies, pledging that purchasing U.S. products would become a core feature of future health assistance, representing a marked departure from needs-based humanitarian procurement.

6. Retreat from multilateral agreements

The decline of multilateralism became a defining trend in 2025. The United States formally gave notice of its withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement, rejoining a small group of countries outside the 2015 accord that aimed to limit global warming.

Washington also announced its exit from the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, citing ideological concerns, and withdrew from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, further weakening multilateral humanitarian mechanisms.

In Latin America, Argentina’s President publicly questioned participation in the Paris Agreement and pulled the country’s delegation from UN climate talks, reflecting growing skepticism toward global frameworks.

7. The forced humanitarian reset

With resources collapsing, the aid system has entered a phase of ‘hyper-prioritization’. By mid-2025, under revised criteria, only 38.3% of people in need, about 114.4 million individuals, were deemed to be eligible for assistance in 2025.

Funding told the same story. Contributions to the Global Humanitarian Overview fell to just US$12 billion, the lowest level in a decade. This shortfall left programs critically underfunded. Ukraine’s appeal was funded at 48.7%, Gaza at 40%, and Sudan at 35.4%, all demonstrating sharp declines from 2024.

The humanitarian system did not simply shrink in 2025; it fractured. What remains is not merely a question of reform, but of survival – whether a system built to respond to human suffering can endure in an era of political retreat, strategic conditionality, and diminishing global solidarity.